What is affordable housing?

Affordable Housing in New York

Text: Schindler, Susanne, Princeton

-

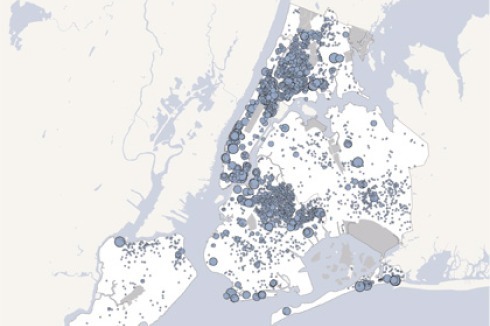

Source: NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development

Source: NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development

-

Areal Picture: NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development

Areal Picture: NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development

A quarter of all New York households already pays more than half of their income for housing. Affordable housing – income-restricted, government-subsidized housing – is the instrument with which, over the course of the past twenty years, entire neighborhoods have been revitalized. What effect does this have on the future of the city? An introduction to terminology, actors, and outcomes.

Richard Plunz’s The History of Housing in New York City (1990), the seminal study of New York housing policy and design to this day, illustrates social change almost entirely by analyzing floor plans. In his epilogue, he points to the growing gap between rich and poor, between the building boom of luxury high-rises in central Manhattan (Donald Trump) and the dev-astation of the outer boroughs (South Bronx) where suburban-style row houses are built in lieu of the abandoned and burned-down six-story apartment buildings. Plunz blames the demise of social housing in New York on a conservative turn in national politics, which shifted the patronage of low- and moderate-income housing to the private sector. He cautions: “A new amalgam of government and private production has yet to materialize on any scale.”

Today, it is no longer just about luxury; brokers use the term “ultra-luxury” to describe apartments in the top five percent segment of the market, or which are selling above 7 million dollars. The conversion of a former residence for young women run by the Salvation Army at 18 Gramercy Park South, a prime Manhattan location, is a perfect illustration of what this means for life in the city. In 2007, a single room with shared bath and two meals a day could be had for 700 dollars a month. In 2008 the property was sold for 60 million dollars. The 300 single rooms are now being replaced by 17 floor-through residences, designed by Robert A.M. Stern for developer W.L. Zeckendorf, the team responsible for the record-setting ultra-luxury building 15 Central Park West, completed in 2007.

Elsewhere, however, the situation could not be more different than what Plunz describes. Walking the South Bronx today means passing new ten-story residential and commercial buildings. In Harlem, the traditional brownstones, mid-nineteenth-century four-story row houses, have been restored, as have the tenement buildings. Between them, high-end new construction has been built. Whether you want to call it revitalization or gentrification: in the mid-1990s it was still impossible to find a supermarket or a bank here. This upswing clearly comes against the backdrop of an overall economic growth. It can also be attributed to the reigning in of crime under mayor Rudolph Giuliani (1994–2001). But studies, for instance by the Furman Center for Urban Real Estate and Policy at New York University, show that the stabilization and economic growth of the city is also the result of the development of housing for low- and moderate-income households, initiated and co-financed by the municipal government.

The City’s active role in housing began in the mid-1980s as mayor Edward Koch (1978–89) was confronted with an enormous stock of real estate which had become public property due to the non-payment of taxes. In the mid-1970s, sixty percent of Central Harlem was City-owned. Koch launched a six-billion-dollar ten-year-plan to rehabilitate this inventory with the goal of selling it to residents or to private developers. His strategy proved successful and was continued in its broad outlines by his successors. Michael Bloomberg, mayor since 2002, set a new benchmark by launching his 8.4-billion-dollar “New Housing Marketplace Plan” with the goal of preserving and creating 165,000 units of affordable housing by 2014. Two-thirds of the goal has been reached today, more or less on schedule despite the economic downturn after 2008.

In the process, the “amalgam of government and private production” Plunz alluded to has come into play involving three main actors: non-profit community development corporations (CDCs), many of which came into being during the fiscal crisis of the 1970s, securing local political participation; for-profit developers, guaranteeing professional implementation; and the municipal government. Accordingly, no one speaks of “social housing” anymore, as Plunz did in 1990. Today it is all about “affordable housing”, implying an altered notion of the role of government. Literally, the term means housing that is affordable to its residents; federal guidelines define housing to be affordable if it consumes no more than a third of a household’s gross income. In practice however, since the 1990s, the term refers to publicly subsidized housing designated for certain income groups at a regulated sales or rental price. The key criterion is the Area Medium Income (AMI), also referred to as Median Family Income (MFI), the median household income of a certain geographic area, recalculated annually by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). In 2011, the AMI for a four-person household in New York City was $80,200. Therefore, if a two-bedroom unit is designated for households earning up to 50 percent AMI, only families with an annual income of up to $40,100 can apply. The sale or rental price is set accordingly and must also be maintained for subsequent residents. Once in an apartment, a resident can generally stay even if the household income rises above the orig-inal limits. A unit’s income-restriction may be unlimited or expire after a certain period of time, depending on funding sources.

In New York City, the lead agency for the construction and supervision of affordable housing is the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD). Through requests for proposals, HPD initiates the development of City-owned land, generally for a mix of affordable and market-rate housing. The land is given away at a symbolic price, and the City, through its Housing Development Corporation (HDC), secures the financing by issuing bonds and providing below-market mortgages. The remaining funding is often secured through Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs), a form of indirect federal subsidies for private investment in affordable housing, and through private banks. In parallel, various mechanisms have evolved to create affordable housing through the private market, such as granting a floor area bonus or extended tax abatements.

Despite all the small government rhetoric in the United States, publically owned and managed housing does still exist, generally known as “public housing”. It is restricted to households making up to 60 percent AMI, and is funded by the federal government and managed by local agencies. While federal budgets have consistently been reduced, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) continues to operate 334 projects serving a total of 400,000 residents. Another component of public housing is the Section 8 voucher program, which subsidizes rents for individuals in the free market. Approximately 235,000 New Yorkers benefit from this program. The demand vastly outweighs the supply: the waiting period for both programs is currently around eight years.

When the scale is right but the typology isn’t

The scale of affordable housing projects emerging in New York is impressive. Often, projects involve entire city blocks as in Harlem’s Bradhurst neighborhood, but entire new neighborhoods are also emerging. Hunter’s Point South is a 12 hectare (30 acre) project on the East River waterfront in Queens; sixty percent of the projected 5,000 housing units will be reserved for household making between 60 and 130 percent AMI. It is astonishing that the City is placing itself in the legacy of the satellite towns of the 1970s, which have long been frowned upon, even if their residents report a high quality of life. As the press releases state: “The largest affordable-housing project since Co-op City and Starrett City.”

The resulting housing, regardless of its being affordable or market-rate, follows only one formula in terms of program and typology, however: the double-loaded corridor in a 60-foot (ca. 18.5 m) deep bar with studios to three-bedroom apartments. Up to twelve stories in height the structural system is block-and-plank: bearing exterior walls with one bearing interior wall made of concrete block supporting pretensioned concrete floor elements. Accordingly, variations between the apartments are limited. Depending on income levels, there are one or two bathrooms, large or small windows, granite or laminate counters. The formula can be expanded through penthouse duplexes or subterranean parking, but the double-load-ed corridor is never challenged. Even in the most politically important showcase projects such as Hunter’s Point South, this basic organizing scheme is defined by the master plan. Even promising architects such as SHoP, only recently involved in affordable housing, cannot change anything here. Their influence is limited to the exterior.

Proponents of this rather banal and ever same solution argue that the double-loaded corridor is the only economical option on the basis of the net-to-gross ratio, the relationship of rentable to non-rentable floor area. The lack of large apartments is attributed to the fact that the subsidies are calculated on a per-unit basis, regardless of the number of bedrooms. Even in Melrose Commons in the South Bronx, where new construction is co-developed by the neighborhood organization “Nos Quedamos” (We are staying) and where there is a known demand for larger apartments due to large families, the response is: Not to be funded! Instead, for-sale row houses are built which include up to two accessory units to make room for extended family or secure the owner’s mortgage through rental income.

The lack of programmatic and typological variation is also due to the fact that in the awarding of projects through HPD, or in the allocation of tax credit funding, team experience and the financial model (the lower the required subsidies, the better) are decisive. With few exceptions, the design proposal is judged only in terms of meeting dimensional and other code requirements. Introducing design competitions to shake up the established ways of doing things or to draw emerging practices to the field is rare. Special selection processes such as those implemented for Via Verde have not been replicated despite the obvious improvements (cross-ventilated units!) in the resulting project.

A central politically fraught issue surrounding affordable housing is the fact that construction costs are often higher than for market-based housing. This is partially due to the fact that contractors working in publicly funded projects must pay a living wage, which is generally about double the minimum wage. Unsubsidized developers can go with the lowest bidder. Furthermore, affordable housing generally requires multiple sources of funding which are sometimes contingent on one another, complicating the administrative process. And then there are questionable minimum standards pertaining to affordable housing that are higher than those in market-rate housing: Why does every apartment need to be at least 400 square feet (ca. 40 square meters) in size and contain a full kitchen?

Long-term affordability, better architecture

Better architecture is, in many ways, a direct result of the de-velopment model. If the client is a non-profit organization that will operate the building with a long-term perspective, chances are good that innovative solutions can be found within the budgetary and regulatory constraints. The six supportive housing projects by Jonathan Kirschenfeld prove the point. If the developer is profit-driven and the project involves no market-rate units at all, the chances for architectural innovation are slim. What New York, and the United States as a whole needs, is a discussion of alternate ways to ensure the long-term affordability of housing. Examples of limited-profit models exist, for instance in the form of community land banks or limited-equity cooperatives. The client’s interest in the long-term quality and economic feasibility of a project has an immediate impact on architectural decisions. In a country that continues to see home ownership as the primary form of individual wealth formation, as well as the basis of a morally responsible citizenry, however, these models are not widely supported. The financial advantages offered to private investors through subsidies are considered more important than the costs incurred by the public sector in doing so: as an example, most housing funded through Low Income Housing Tax Credits must remain income-restricted for only 15 years.

We need to acknowledge that securing affordable housing, in the literal sense of the word, is only possible with subsidies – not only for low- and middle-income households but, as New York shows, even for households earning far be-yond the average. In order to make the point politically, it helps to recall that all housing – from infrastructure-intensive suburban development to tax-abatement supported luxury highrise construction – is directly or indirectly funded by the public sector. The Center for Urban Pedagogy summarizes it best: “Almost all affordable housing is subsidized, but not all subsidized housing is affordable.”

Richard Plunz’s The History of Housing in New York City (1990), the seminal study of New York housing policy and design to this day, illustrates social change almost entirely by analyzing floor plans. In his epilogue, he points to the growing gap between rich and poor, between the building boom of luxury high-rises in central Manhattan (Donald Trump) and the devastation of the outer boroughs (South Bronx) where suburban-style row houses are built in lieu of the abandoned and burned-down six-story apartment buildings. Plunz blames the demise of social housing in New York on a conservative turn in national politics, which shifted the patronage of low- and moderate-income housing to the private sector. He cautions: “A new amalgam of government and private production has yet to materialize on any scale.”

Today, it is no longer just about luxury; brokers use the term “ultra-luxury” to describe apartments in the top five percent segment of the market, or which are selling above 7 million dollars. The conversion of a former residence for young women run by the Salvation Army at 18 Gramercy Park South, a prime Manhattan location, is a perfect illustration of what this means for life in the city. In 2007, a single room with shared bath and two meals a day could be had for 700 dollars a month. In 2008 the property was sold for 60 million dollars. The 300 single rooms are now being replaced by 17 floor-through residences, designed by Robert A.M. Stern for developer W.L. Zeckendorf, the team responsible for the record-setting ultra-luxury building 15 Central Park West, completed in 2007.

Elsewhere, however, the situation could not be more different than what Plunz describes. Walking the South Bronx today means passing new ten-story residential and commercial buildings. In Harlem, the traditional brownstones, mid-nineteenth-century four-story row houses, have been restored, as have the tenement buildings. Between them, high-end new construction has been built. Whether you want to call it revitalization or gentrification: in the mid-1990s it was still impossible to find a supermarket or a bank here. This upswing clearly comes against the backdrop of an overall economic growth. It can also be attributed to the reigning in of crime under mayor Rudolph Giuliani (1994–2001). But studies, for instance by the Furman Center for Urban Real Estate and Policy at New York University, show that the stabilization and economic growth of the city is also the result of the development of housing for low- and moderate-income households, initiated and co-financed by the municipal government.

The City’s active role in housing began in the mid-1980s as mayor Edward Koch (1978–89) was confronted with an enormous stock of real estate which had become public property due to the non-payment of taxes. In the mid-1970s, sixty percent of Central Harlem was City-owned. Koch launched a six-billion-dollar ten-year-plan to rehabilitate this inventory with the goal of selling it to residents or to private developers. His strategy proved successful and was continued in its broad outlines by his successors. Michael Bloomberg, mayor since 2002, set a new benchmark by launching his 8.4-billion-dollar “New Housing Marketplace Plan” with the goal of preserving and creating 165,000 units of affordable housing by 2014. Two-thirds of the goal has been reached today, more or less on schedule despite the economic downturn after 2008.

In the process, the “amalgam of government and private production” Plunz alluded to has come into play involving three main actors: non-profit community development corporations (CDCs), many of which came into being during the fiscal crisis of the 1970s, securing local political participation; for-profit developers, guaranteeing professional implementation; and the municipal government. Accordingly, no one speaks of “social housing” anymore, as Plunz did in 1990. Today it is all about „affordable housing,“ implying an altered notion of the role of government. Literally, the term means housing that is affordable to its residents; federal guidelines define housing to be affordable if it consumes no more than a third of a household’s gross income. In practice however, since the 1990s, the term refers to publically subsidized housing designated for certain income groups at a regulated sales or rental price. The key criterion is the Area Medium Income (AMI), also referred to as Median Family Income (MFI), the median household income of a certain geographic area, recalculated annually by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). In 2011, the AMI for a four-person household in New York City was $80,200. Therefore, if a two-bedroom unit is designated for households earning up to 50 percent AMI, only families with an annual income of up to $40,100 can apply. The sale or rental price is set accordingly and must also be maintained for subsequent residents. Once in an apartment, a resident can generally stay even if the household income rises above the original limits. A unit’s income-restriction may be unlimited or expire after a certain period of time, depending on funding sources.

In New York City, the lead agency for the construction and supervision of affordable housing is the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD). Through requests for proposals, HPD initiates the development of City-owned land, generally for a mix of affordable and market-rate housing. The land is given away at a symbolic price, and the City, through its Housing Development Corporation (HDC), secures the financing by issuing bonds and providing below-market mortgages. The remaining funding is often secured through Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs), a form of indirect federal subsidies for private investment in affordable housing, and through private banks. In parallel, various mechanisms have evolved to create affordable housing through the private market, such as granting a floor area bonus or extended tax abatements.

Despite all the small government rhetoric in the United States, publically owned and managed housing does still exist, generally known as “public housing”. It is restricted to households making up to 60 percent AMI, and is funded by the federal government and managed by local agencies. While federal budgets have consistently been reduced, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) continues to operate 334 projects serving a total of 400,000 residents. Another component of public housing is the Section 8 voucher program, which subsidizes rents for individuals in the free market. Approximately 235,000 New Yorkers benefit from this program. The demand vastly outweighs the supply: the waiting period for both programs is currently around eight years.

When the scale is right but the typology isn’t

The scale of affordable housing projects emerging in New York is impressive. Often, projects involve entire city blocks as in Harlem’s Bradhurst neighborhood, but entire new neighborhoods are also emerging. Hunter’s Point South is a 12 hectare (30 acre) project on the East River waterfront in Queens; sixty percent of the projected 5,000 housing units will be reserved for household making between 60 and 130 percent AMI. It is astonishing that the City is placing itself in the legacy of the satellite towns of the 1970s, which have long been frowned upon, even if their residents report a high quality of life. As the press releases state: “The largest affordable-housing project since Co-op City and Starrett City.”

The resulting housing, regardless of its being affordable or market-rate, follows only one formula in terms of program and typology, however: the double-loaded corridor in a 60-foot (ca. 18.5 m) deep bar with studios to three-bedroom apartments. Up to twelve stories in height the structural system is block-and-plank: bearing exterior walls with one bearing interior wall made of concrete block supporting pretensioned concrete floor elements. Accordingly, variations between the apartments are limited. Depending on income levels, there are one or two bathrooms, large or small windows, granite or laminate counters. The formula can be expanded through penthouse duplexes or subterranean parking, but the double-loaded corridor is never challenged. Even in the most politically important showcase projects such as Hunter’s Point South, this basic organizing scheme is defined by the master plan. Even promising architects such as SHoP, only recently involved in affordable housing, cannot change anything here. Their influence is limited to the exterior.

Proponents of this rather banal and ever same solution argue that the double-loaded corridor is the only economical option on the basis of the net-to-gross ratio, the relationship of rentable to non-rentable floor area. The lack of large apartments is attributed to the fact that the subsidies are calculated on a per-unit basis, regardless of the number of bedrooms. Even in Melrose Commons in the South Bronx, where new construction is co-developed by the neighborhood organization “Nos Quedamos” (We are staying) and where there is a known demand for larger apartments due to large families, the response is: Not to be funded! Instead, for-sale row houses are built which include up to two accessory units to make room for extended family or secure the owner’s mortgage through rental income.

The lack of programmatic and typological variation is also due to the fact that in the awarding of projects through HPD, or in the allocation of tax credit funding, team experience and the financial model (the lower the required subsidies, the better) are decisive. With few exceptions, the design proposal is judged only in terms of meeting dimensional and other code requirements. Introducing design competitions to shake up the established ways of doing things or to draw emerging practices to the field is rare. Special selection processes such as those implemented for Via Verde have not been replicated despite the obvious improvements (cross-ventilated units!) in the resulting project.

A central politically fraught issue surrounding afford-able housing is the fact that construction costs are often higher than for market-based housing. This is partially due to the fact that contractors working in publicly funded projects must pay a living wage, which is generally about double the minimum wage. Unsubsidized developers can go with the lowest bidder. Furthermore, affordable housing generally requires multiple sources of funding which are sometimes contingent on one another, complicating the administrative process. And then there are questionable minimum standards pertaining to affordable housing that are higher than those in market-rate housing: Why does every apartment need to be at least 400 square feet (ca. 40 square meters) in size and contain a full kitchen?

Long-term affordability, better architecture

Better architecture is, in many ways, a direct result of the de-velopment model. If the client is a non-profit organization that will operate the building with a long-term perspective, chances are good that innovative solutions can be found within the budgetary and regulatory constraints. The six supportive housing projects by Jonathan Kirschenfeld prove the point. If the developer is profit-driven and the project involves no market-rate units at all, the chances for architectural innovation are slim. What New York, and the United States as a whole needs, is a discussion of alternate ways to ensure the long-term affordability of housing. Examples of limited-profit models exist, for instance in the form of community land banks or limited-equity cooperatives. The client’s interest in the long-term quality and economic feasibility of a project has an immediate impact on architectural decisions. In a country that continues to see home ownership as the primary form of individual wealth formation, as well as the basis of a morally responsible citizenry, however, these models are not widely supported. The financial advantages offered to private investors through subsidies are considered more important than the costs incurred by the public sector in doing so: as an example, most housing funded through Low Income Housing Tax Credits must remain income-restricted for only 15 years.

We need to acknowledge that securing affordable housing, in the literal sense of the word, is only possible with subsidies – not only for low- and middle-income households but, as New York shows, even for households earning far be-yond the average. In order to make the point politically, it helps to recall that all housing – from infrastructure-intensive suburban development to tax-abatement supported luxury highrise construction - is directly or indirectly funded by the public sector. The Center for Urban Pedagogy summarizes it best: “Almost all affordable housing is subsidized, but not all subsidized housing is affordable.”

x

Bauwelt Newsletter

Immer freitags erscheint der Bauwelt-Newsletter mit dem Wichtigsten der Woche: Lesen Sie, worum es in der neuen Ausgabe geht. Außerdem:

- » aktuelle Stellenangebote

- » exklusive Online-Beiträge, Interviews und Bildstrecken

- » Wettbewerbsauslobungen

- » Termine

- » Der Newsletter ist selbstverständlich kostenlos und jederzeit wieder kündbar.

Beispiele, Hinweise: Datenschutz, Analyse, Widerruf

0 Kommentare