The other side of the coin: Reading the Riots

London 2012

Text: Till, Jeremy, London

The other side of the coin: Reading the Riots

London 2012

Text: Till, Jeremy, London

London 2011 – almost exactly a year before the Olympics, shocking pictures were seen around the world. They showed rampaging youths, burning high streets and a powerless police. What pattern is revealed by the London disturbances? What were the reasons for the riots? And how do we prevent such events from being repeated?

Spatially, riots may be placed into two broad categories. First the riots that take place within the most socially deprived areas and are defined by their boundaries. Second riots that take place in city centres, bringing the excluded directly into confrontation with the spaces they are normally excluded from. The first group includes the Broadwater Farm riot of 1985, the Los Angeles riots of 1992, and the Parisian banlieue riots of 2005. The second group includes the Manchester riots of 2011, the London Poll Tax riots of 1989 and the Detroit riots of 1967, (which started with a local altercation but rapidly, spread out to the neighboring University district). The first group of riots are the most easy for the establishment to manage, both practically (because they can be contained) and politically (because there is always, close to the surface, the implication that this is what poor/black/unemployed people do, and it can’t be helped).

Out of sight, out of mind, the peripheral riots are less of a worry to the mainstream: with the dispossessed just beating each other up and destroying their own worlds, the rest of us can carry on relatively untroubled. The second set of riots, those which take on the centre spatially and conceptually, are more of a problem, which is why they are treated with such institutional ferocity, for example in the Poll Tax riots in London’s Trafalgar Square, or when an initially peaceful demonstration that presents the merest threat of escalation is subjected to techniques such as kettling in the 2010 London student demonstrations and the spraying of mace on innocent women in the 2011 Occupy Wall Street events. But in presenting such an affront to the establishment, the rampant riots in the centre also tend to effect real change. Thus the Poll Tax riots are largely seen as a lever in the fall of Margaret Thatcher, and the Detroit riots led to a tripling of outward migration of whites from the city.

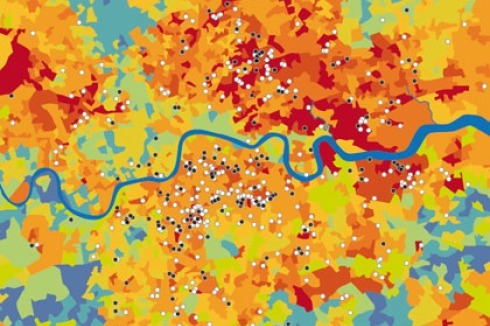

The maps of the London riots, however, fit neither of these patterns. With one conspicuous exception, they were not concentrated in the heart of an area with the highest social deprivation nor do they occur in the city centre; they are dispersed across the city, and the majority of the riots are located on the boundaries of areas of differing social indicators. The exception is Tottenham, where the initial riot broke out. The focused trigger for that (the protest against the killing by the police of Mark Duggan) was very different from eruptions on subsequent nights, which were precipitated in a seemingly arbitrary manner. If Tottenham was contained within an area of high social deprivation, in the manner of previous riots, the subsequent ones occurred at points where different demographics rubbed up against each other. Fault lines is probably too sensational a term, because it suggests places of radical difference waiting to erupt as the almost inevitable outcome of social or spatial conditioning. London boundaries are less exceptional – until quite recently it was rare to see gated communities or other aspects of clear socio-spatial segregation.

London does indeed have the broadest spread on social indicator scales, containing the very rich and the very poor, but these differences are not expressed as clearly as in other cities, where typically the rich and poor dwell apart in clearly defined areas. The London map of social deprivation reads as a restless patchwork rather than as a set of neat zones. In many ways it is exactly this mix that gives the city its vibrancy and diversity. But, it would appear, it is also this mix that underscored the 2011 London riots. In contrast, the maps of the other cities where the 2011 riots took place (Birmingham, Manchester and Nottingham) show a more conventional demarcation between centre, poor areas and rich areas. In these cities the riots generally followed the bipolar pattern of being located either in the centre or the most deprived areas. In London the pattern of the underlying social deprivation is different, and so also, it appears, is the pattern of the rioting.

Extreme action in everyday spaces

The London map shows that the riots did not occur in places defined by their difference from the norm – the grand centre or the excluded margin – but in places characterized by their ordinariness. The slightly down-at-heel high street location of most of the riots is so typical of London that its citizens take it for granted, quietly enjoying the muddle of ethnic shops, nail parlours, discount shoe shops, pound stores and so on. Although often existing on marginal economies, and used by the socially excluded, these high streets are very different from the contained pockets of poverty that were the focus of riots in other cities; they are connected and diverse where the latter are isolated and homogenous. These streets are not the centres of civic life in terms of the grand public institutions of the city centre, nor of business life, in the sense of the central business districts of the modern city; rather, they are the nexus of ordinary life, of daily shopping, of local trades, and day-to-day socializing. As such they provide a vestige of public space that has largely been eradicated from the rest of our cities. Surveilled they might be, but they are not locked away from the rest of the city. ‘Higher’ commerce has been removed and corralled into the privatized shopping centres. One makes special trips to shopping centres, whereas the local street is just there, available as a setting for everyday life; available, it transpires, as a setting for rioting.

What the riots did was to collapse the distance between the extraordinary and the ordinary, with extreme action happening in the most everyday of spaces. As Sam Jacob has argued, the riots “transformed everyday urban activities into an exceptional state of unlawfulness”. The almost hysterical reaction to the riots may be attributed to this overlaying of the extraordinary on the ordinary: the unpredictability of their inception and the feeling that they could happen almost anywhere – ‘at the end of my street’, one heard so many people say at the time – led to an understandable fear and sense of unease. This sense of unease was exacerbated by the dispersal, speed and fluidity of the riots. The London riots were not centred on a particular space or object: as Jacob notes, “while the traditional form of riot has a target, here it was centreless, with no middle and no edge”.

The cul-de-sac of architectural determinism

Unregarded of this unpredictability, many commentators tried to find a form of spatial determinism in the pattern of the riots. Like in the London Broadwater Farm riots of 1985, where a whole series of people weighed in to make the association between decaying estates and the ‘resulting’ riots, in 2011 the analysts of Space Syntax implied a causal link between the spatiality of post-war housing estates and the act of rioting. This architectural determinism, which all too conveniently overlooks the political and social, plays into the hands of politicians who are all too glad to have other factors as an explanation of social disturbance. Architectural arrogance, spatial complexity, blind alleys – all these and more shift the responsibility out of political hands and onto other more instrumental factors.

Let’s use Georg Simmel to reverse out of this cul-de-sac of architectural determinism: “the city is not a spatial entity with sociological consequences, but a sociological entity that is formed spatially”. In their matching of the haphazard, dispersed and diverse spatiality of the everyday city, the London riots can clearly be read as the “intensification of an underlying situation”. The riots were not an event in a space or time set apart – they even started to take place by day, countering the more typical manifestation of night-time riots, in which flames, silhouettes and partial vision combine into a filmic spectacle of fear and apocalypse. No, the London riots were a magnification of what was there already. It is this that made them so unsettling at the time, and it is this that gives them such a menacing legacy. There is a continuing apprehension that if, apart from initial shooting of Mark Duggan, the other riots started with such apparent ease and randomness, what is to stop them erupting again? What might be the next trigger for the intensification of the underlying? And if they do erupt again, then what might stop them?

Targeted riots bring with them the solution in the form of getting rid of or dissolving the target: Council Tax replaces Poll Tax, Broadwater Farm is given a social and spatial makeover. However, these London riots in all their banality and lack of clear target are much less easy to address. Hence their reduction by politicians to ‘criminality, pure and simple’, because criminality can be ‘simply’ dealt with through the law. And hence their reduction by Space Syntax to spatial determinism, because that sows the seeds of a spatial solution. In the end a combination of mass arrests, citizen action and media outcry on the one hand, and a sense of dwindling energy and opportunity on the other (after all there is no adrenalin rush in beating up the same sad street more than once), meant that the London riots petered out after four days, but this is hardly a longterm or sustainable solution.

The broken middle

The location of the riots along the seams of the patchwork of the map of social deprivation suggests the problem is more complex than if they were located in the middle of blocks of homogenous social deprivation. In the middle, the issue of cause and effect is containable and potentially treatable. Along the seams it is less easy to pin down. Seams both join and separate the pieces of a patchwork, and in this duality are different to traditional borders, which only separate and have conditions for crossing. The seams of social deprivation trace rhizomically across the map of London, the legacy of migration, joining-up of villages, grouping around trading centres, food supply and myriad other historical traits. The riots did not occur where the very red (the poorest) come against the very blue (the richest); if they had, then we could have read them as a form of class war. Equally if the targets had been the emporia of the rich, we could have read the riots as a form of plebian revolt, or if the institutions of the powerful, as a form of revolutionary action. Instead the riots happened along streets and in stores that were known to the rioters as part of their everyday life; not an exceptional revolution but an all-but-normal eruption. They took place along the seams between sometimes only marginally differentiated demographics, and the targets were the stores of mass produced consumer goods (trainers, flat screen televisions) and distraction (alcohol, computer games).

This leads us to other readings than the simple them and us. First, the rhizomic seams in their ambiguity of joining and separating, and in their provisionality as demarcations, provide a perfect setting for the fluid and open-ended maneuvers that took place along them. The form of the riots is conjoined with the form of the space; whilst the spatiality of the seams clearly did not cause the riots, it certainly enabled their very particular character to develop. Secondly, the location on the boundaries of differing social deprivation suggest that the riots were at heart a spatialisation of the ramping up of social inequality. In the 2000s, social indices showed a stretching of the line between those who have and those that don’t. The London riots did not bring the ends of the line into confrontation, rather they operated along its now extended length, in which differences were, and are, ever more exaggerated. The locations of the riots were at places where the line of social inequality was stretched to breaking; not at the extremes, but in the spaces where previously benign normality had been distorted by the fatal intersection of the scarcity of means and abundance of desire, the latter driven by the prevailing spectacle of consumption.

If Zygmunt Bauman is right in identifying a “combination of consumerism with rising inequality” as the backdrop to the riots, then these humdrum London streets of the broken middle become their natural location. Shepherded and monitored in the privatized spaces of shopping malls and alienated by the civic spaces of the city centre, the dispossessed gravitated towards the easy targets of the possessors. The high street is the perfect territory for the riots in providing the booty and also in their joining-separating role – both providing smooth connections in and out to other areas, and giving enough frisson in their division between somewhat, but not totally, demarcated areas.

An unacceptable truth

The implications of this interpretation are sobering. The riots emerged in the bits of the city that have escaped privatization, and which retain, despite surveillance and policing, a public life of the everyday. To say that the riots are the price that we have to pay if we want to maintain any semblance of public life is to suggest an awful, and publicly unacceptable, truth. To embrace civic space we have to accept conflict within it. The broken middle where the riots erupted is not easily fixed; social inequality is stretching not reducing, the spectacle of consumption ever more shiny. The conditions remain in place for the intensification of the everyday to reemerge at any point. The knee jerk reaction is to tighten the grip on those spaces – to police them more, to introduce more surveillance, to further privatize them. However, my interpretation points in exactly the opposite direction. We need more urban freedom, not less, if we are going to dissipate the fury of inequality.

All the indicators are that the official response is exactly the opposite, with rioters being made homeless, call for more street security and the inevitable roll out of yet more CCTV. But this will only tighten the knot around an already squeezed sector of society, potentially exacerbating the next response. The choice of operations on the broken middle is to either further fracture it by erecting spatial barriers between its constituent parts, or else to accept the patchwork for what it is (a healthy and honest spatial mix) and reinvest it with more, not less, genuinely public space. Clearly the political solution to the reduction of social inequality is out of the direct hands of urbanists, but we do have the opportunity, and I would argue responsibility, to be brave in resisting the calls for ever firmer lines of demarcation and ever more tools of urban control.

Out of sight, out of mind, the peripheral riots are less of a worry to the mainstream: with the dispossessed just beating each other up and destroying their own worlds, the rest of us can carry on relatively untroubled. The second set of riots, those which take on the centre spatially and conceptually, are more of a problem, which is why they are treated with such institutional ferocity, for example in the Poll Tax riots in London’s Trafalgar Square, or when an initially peaceful demonstration that presents the merest threat of escalation is subjected to techniques such as kettling in the 2010 London student demonstrations and the spraying of mace on innocent women in the 2011 Occupy Wall Street events. But in presenting such an affront to the establishment, the rampant riots in the centre also tend to effect real change. Thus the Poll Tax riots are largely seen as a lever in the fall of Margaret Thatcher, and the Detroit riots led to a tripling of outward migration of whites from the city.

The maps of the London riots, however, fit neither of these patterns. With one conspicuous exception, they were not concentrated in the heart of an area with the highest social deprivation nor do they occur in the city centre; they are dispersed across the city, and the majority of the riots are located on the boundaries of areas of differing social indicators. The exception is Tottenham, where the initial riot broke out. The focused trigger for that (the protest against the killing by the police of Mark Duggan) was very different from eruptions on subsequent nights, which were precipitated in a seemingly arbitrary manner. If Tottenham was contained within an area of high social deprivation, in the manner of previous riots, the subsequent ones occurred at points where different demographics rubbed up against each other. Fault lines is probably too sensational a term, because it suggests places of radical difference waiting to erupt as the almost inevitable outcome of social or spatial conditioning. London boundaries are less exceptional – until quite recently it was rare to see gated communities or other aspects of clear socio-spatial segregation.

London does indeed have the broadest spread on social indicator scales, containing the very rich and the very poor, but these differences are not expressed as clearly as in other cities, where typically the rich and poor dwell apart in clearly defined areas. The London map of social deprivation reads as a restless patchwork rather than as a set of neat zones. In many ways it is exactly this mix that gives the city its vibrancy and diversity. But, it would appear, it is also this mix that underscored the 2011 London riots. In contrast, the maps of the other cities where the 2011 riots took place (Birmingham, Manchester and Nottingham) show a more conventional demarcation between centre, poor areas and rich areas. In these cities the riots generally followed the bipolar pattern of being located either in the centre or the most deprived areas. In London the pattern of the underlying social deprivation is different, and so also, it appears, is the pattern of the rioting.

Extreme action in everyday spaces

The London map shows that the riots did not occur in places defined by their difference from the norm – the grand centre or the excluded margin – but in places characterized by their ordinariness. The slightly down-at-heel high street location of most of the riots is so typical of London that its citizens take it for granted, quietly enjoying the muddle of ethnic shops, nail parlours, discount shoe shops, pound stores and so on. Although often existing on marginal economies, and used by the socially excluded, these high streets are very different from the contained pockets of poverty that were the focus of riots in other cities; they are connected and diverse where the latter are isolated and homogenous. These streets are not the centres of civic life in terms of the grand public institutions of the city centre, nor of business life, in the sense of the central business districts of the modern city; rather, they are the nexus of ordinary life, of daily shopping, of local trades, and day-to-day socializing. As such they provide a vestige of public space that has largely been eradicated from the rest of our cities. Surveilled they might be, but they are not locked away from the rest of the city. ‘Higher’ commerce has been removed and corralled into the privatized shopping centres. One makes special trips to shopping centres, whereas the local street is just there, available as a setting for everyday life; available, it transpires, as a setting for rioting.

What the riots did was to collapse the distance between the extraordinary and the ordinary, with extreme action happening in the most everyday of spaces. As Sam Jacob has argued, the riots “transformed everyday urban activities into an exceptional state of unlawfulness”. The almost hysterical reaction to the riots may be attributed to this overlaying of the extraordinary on the ordinary: the unpredictability of their inception and the feeling that they could happen almost anywhere – ‘at the end of my street’, one heard so many people say at the time – led to an understandable fear and sense of unease. This sense of unease was exacerbated by the dispersal, speed and fluidity of the riots. The London riots were not centred on a particular space or object: as Jacob notes, “while the traditional form of riot has a target, here it was centreless, with no middle and no edge”.

The cul-de-sac of architectural determinism

Unregarded of this unpredictability, many commentators tried to find a form of spatial determinism in the pattern of the riots. Like in the London Broadwater Farm riots of 1985, where a whole series of people weighed in to make the association between decaying estates and the ‘resulting’ riots, in 2011 the analysts of Space Syntax implied a causal link between the spatiality of post-war housing estates and the act of rioting. This architectural determinism, which all too conveniently overlooks the political and social, plays into the hands of politicians who are all too glad to have other factors as an explanation of social disturbance. Architectural arrogance, spatial complexity, blind alleys – all these and more shift the responsibility out of political hands and onto other more instrumental factors.

Let’s use Georg Simmel to reverse out of this cul-de-sac of architectural determinism: “the city is not a spatial entity with sociological consequences, but a sociological entity that is formed spatially”. In their matching of the haphazard, dispersed and diverse spatiality of the everyday city, the London riots can clearly be read as the “intensification of an underlying situation”. The riots were not an event in a space or time set apart – they even started to take place by day, countering the more typical manifestation of night-time riots, in which flames, silhouettes and partial vision combine into a filmic spectacle of fear and apocalypse. No, the London riots were a magnification of what was there already. It is this that made them so unsettling at the time, and it is this that gives them such a menacing legacy. There is a continuing apprehension that if, apart from initial shooting of Mark Duggan, the other riots started with such apparent ease and randomness, what is to stop them erupting again? What might be the next trigger for the intensification of the underlying? And if they do erupt again, then what might stop them?

Targeted riots bring with them the solution in the form of getting rid of or dissolving the target: Council Tax replaces Poll Tax, Broadwater Farm is given a social and spatial makeover. However, these London riots in all their banality and lack of clear target are much less easy to address. Hence their reduction by politicians to ‘criminality, pure and simple’, because criminality can be ‘simply’ dealt with through the law. And hence their reduction by Space Syntax to spatial determinism, because that sows the seeds of a spatial solution. In the end a combination of mass arrests, citizen action and media outcry on the one hand, and a sense of dwindling energy and opportunity on the other (after all there is no adrenalin rush in beating up the same sad street more than once), meant that the London riots petered out after four days, but this is hardly a longterm or sustainable solution.

The broken middle

The location of the riots along the seams of the patchwork of the map of social deprivation suggests the problem is more complex than if they were located in the middle of blocks of homogenous social deprivation. In the middle, the issue of cause and effect is containable and potentially treatable. Along the seams it is less easy to pin down. Seams both join and separate the pieces of a patchwork, and in this duality are different to traditional borders, which only separate and have conditions for crossing. The seams of social deprivation trace rhizomically across the map of London, the legacy of migration, joining-up of villages, grouping around trading centres, food supply and myriad other historical traits. The riots did not occur where the very red (the poorest) come against the very blue (the richest); if they had, then we could have read them as a form of class war. Equally if the targets had been the emporia of the rich, we could have read the riots as a form of plebian revolt, or if the institutions of the powerful, as a form of revolutionary action. Instead the riots happened along streets and in stores that were known to the rioters as part of their everyday life; not an exceptional revolution but an all-but-normal eruption. They took place along the seams between sometimes only marginally differentiated demographics, and the targets were the stores of mass produced consumer goods (trainers, flat screen televisions) and distraction (alcohol, computer games).

This leads us to other readings than the simple them and us. First, the rhizomic seams in their ambiguity of joining and separating, and in their provisionality as demarcations, provide a perfect setting for the fluid and open-ended maneuvers that took place along them. The form of the riots is conjoined with the form of the space; whilst the spatiality of the seams clearly did not cause the riots, it certainly enabled their very particular character to develop. Secondly, the location on the boundaries of differing social deprivation suggest that the riots were at heart a spatialisation of the ramping up of social inequality. In the 2000s, social indices showed a stretching of the line between those who have and those that don’t. The London riots did not bring the ends of the line into confrontation, rather they operated along its now extended length, in which differences were, and are, ever more exaggerated. The locations of the riots were at places where the line of social inequality was stretched to breaking; not at the extremes, but in the spaces where previously benign normality had been distorted by the fatal intersection of the scarcity of means and abundance of desire, the latter driven by the prevailing spectacle of consumption.

If Zygmunt Bauman is right in identifying a “combination of consumerism with rising inequality” as the backdrop to the riots, then these humdrum London streets of the broken middle become their natural location. Shepherded and monitored in the privatized spaces of shopping malls and alienated by the civic spaces of the city centre, the dispossessed gravitated towards the easy targets of the possessors. The high street is the perfect territory for the riots in providing the booty and also in their joining-separating role – both providing smooth connections in and out to other areas, and giving enough frisson in their division between somewhat, but not totally, demarcated areas.

An unacceptable truth

The implications of this interpretation are sobering. The riots emerged in the bits of the city that have escaped privatization, and which retain, despite surveillance and policing, a public life of the everyday. To say that the riots are the price that we have to pay if we want to maintain any semblance of public life is to suggest an awful, and publicly unacceptable, truth. To embrace civic space we have to accept conflict within it. The broken middle where the riots erupted is not easily fixed; social inequality is stretching not reducing, the spectacle of consumption ever more shiny. The conditions remain in place for the intensification of the everyday to reemerge at any point. The knee jerk reaction is to tighten the grip on those spaces – to police them more, to introduce more surveillance, to further privatize them. However, my interpretation points in exactly the opposite direction. We need more urban freedom, not less, if we are going to dissipate the fury of inequality.

All the indicators are that the official response is exactly the opposite, with rioters being made homeless, call for more street security and the inevitable roll out of yet more CCTV. But this will only tighten the knot around an already squeezed sector of society, potentially exacerbating the next response. The choice of operations on the broken middle is to either further fracture it by erecting spatial barriers between its constituent parts, or else to accept the patchwork for what it is (a healthy and honest spatial mix) and reinvest it with more, not less, genuinely public space. Clearly the political solution to the reduction of social inequality is out of the direct hands of urbanists, but we do have the opportunity, and I would argue responsibility, to be brave in resisting the calls for ever firmer lines of demarcation and ever more tools of urban control.

0 Kommentare